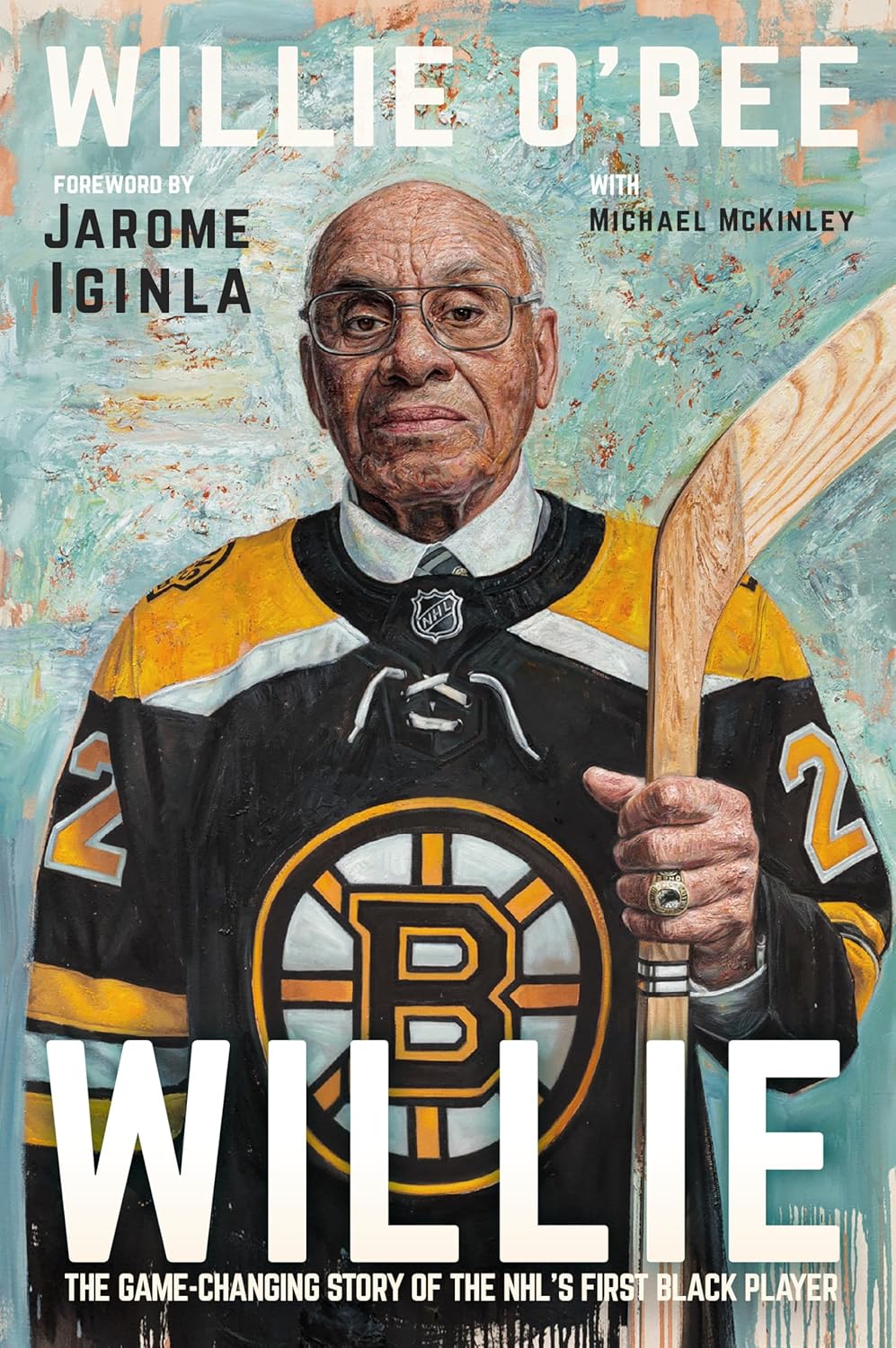

Willie: The Game-Changing Story of the NHL’s First Black Player by Willie O’Ree with Michael McKinley was a rapid read that was a pleasure to sit with for hours at a time. O’Ree told his story starting with his ancestor Paris O’Ree, who escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad in the late eighteenth century. He then devoted a paragraph to each succeeding generation until he arrived at his father. The story flowed like a long interview transcription, and whether it was O’Ree’s storytelling ability or McKinley’s skill at piecing interview bits together–likely both–Willie was a can’t-put-down read.

O’Ree loved to play hockey from a young age, and played on outdoor rinks and then in New Brunswick leagues, gradually making his way up the hockey hierarchy, eventually achieving his goal of playing in the NHL. He played for the Boston Bruins starting in 1958 and remained in the NHL until 1961.

What struck me from the start of the book was O’Ree’s sense of optimism and positivity. He acknowledges that while racist taunts from spectators stung his ears, he never let it bring him down or make him question his position in hockey. He had close bonds with his teammates, and over and over O’Ree said that once he was part of a team, race didn’t matter. They were all in the game and had to work together. His friendship with Bruins left winger Johnny Bucyk is told with such heartfelt fondness it nearly brought tears to my eyes.

O’Ree played professionally until 1979 and then embarked on a new career in security. In 1998 the NHL asked him to come aboard as part of their new diversity task force, in an attempt to broaden the appeal of hockey and make it more inclusive. His work in this field over twenty years saw O’Ree inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018.

Willie was full of inspirational passages and quotes that I am reproducing below.

“I sometimes wonder whether my life would have been different, or somehow felt different, if I’d grown up watching [Rocket] Richard and other NHLers on television. That is, if I saw what they looked like. I never saw the red, white, and blue of the Habs sweaters, but I also never saw black and white–because it wasn’t there for me to see. All I ever imagined as a kid was the game itself. The question of color was never part of it. It’s interesting to think that the tradition of Hockey Night in Canada on the family radio, which was so much a part of Canadians’ lives back then, allowed me to imagine a version of the game that had a place for a player like me.”

O’Ree has often been called the Jackie Robinson of hockey. What I didn’t know was that O’Ree was also a budding baseball player, and played during the hockey off-season. He had the opportunity to meet Robinson, and wrote of their interaction:

“After the game we gathered in the Dodgers’ dugout and met Robinson himself. He could not have been nicer, asking each of us our name and whether we liked baseball. When my turn came, I told him that I liked baseball a lot but that I liked hockey more. He looked surprised and said that hockey didn’t have any black players. I told him he was looking at one, and that he’d see me make my mark on the game the way he’d made his on baseball.”

While O’Ree was playing baseball in the American south, he experienced the worst taunts from racist ball fans and even other players. Throughout the book O’Ree looked back on his life and the discrimination he had faced, and nothing compared to the epithets thrown at him while playing ball in the southern states. His white teammates had his back when his entire team walked out when a segregated establishment refused him entry:

“The next week we played an exhibition game and I got a couple of hits, but what was new to me were the racial jeers from the white players, both in the camp and on outside teams. I let it go in one ear and out the other, but I’d never experienced anything like that from my hockey player teammates in Canada.”

This book was a cherished read for all the wisdom O’Ree imparts. I learned more about resilience, conviction and confidence from this sports hero. In the rough-and-tumble world of professional hockey, trash talking and “chirping” are part of the game–yet racist jabs aren’t. O’Ree knows the difference:

“Trash talking aims to needle an opponent by casting doubt on his strength or his intelligence or his girlfriend, but within the context of the game. Racism aims to diminish the humanity of a person, period. It’s not about a game, it’s about your life. There’s a huge difference, as anyone who’s ever been racially abused will tell you.”

As we celebrate Black History Month I recommend Willie as a must-read.

Find this book in the Mississauga Library System's on-line catalogue