Early into the book he analyzes Cut Piece, Yoko’s most famous piece of performance art. In this piece, she sits silently on stage after inviting members of the audience to come up and cut off pieces of her clothing. She has performed this piece numerous times on three continents, most recently in 2003 at the age of seventy. Here is a woman who had no issue whatsoever with public nudity, as only three years after the clip below, she was posing nude with John Lennon on the cover of Two Virgins. Brackett’s examination of Cut Piece was poignant and spot-on:

“Now considered a classic of feminist art, Cut Piece was possibly Yoko’s most daring public performance piece ever. Her chief raw material for the act was ‘some anger and turbulence in my heart,’ she later told Record Collector magazine. The intensity of feeling generated by the piece would stay with her: ‘That was a frightening experience, and a bit embarrassing. It was something that I insisted on–in the Zen tradition of doing the thing which is the most embarrassing for you to do, and seeing what you come up with and how you deal with it.'”

Brackett provided a history of Ono’s early performance pieces, happenings, gallery shows and written works. Readers who were led to believe that Ono only started to get into art and music after she met John Lennon would be shocked to learn how far back her art history goes. Lennon was still a teenager when she was starting to make a name for herself.

However when he examined Ono’s musical oeuvre his writing was less inspired and, his alleged facts, at times, were unfortunately incorrect. He often got dates wrong (the photos insert was rife with anachronisms) and he assigned songs to the wrong albums, however two specific errors ruined the overall academic tone of the book, such as referring to Gibraltar as an island, and the misspelling Ghandi (embarrassingly, twice).

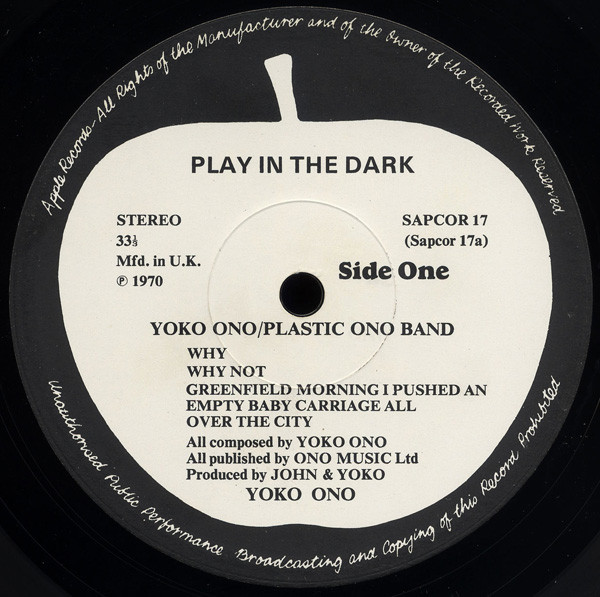

If Brackett was more qualified to critique Ono as an artist, at least he sought others to evaluate her as a musician, and even then sometimes erred when he himself was praising her. For example, in his critique of what I consider to be Ono’s single best song ever, “Why” (from her debut album Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band), Brackett is mistaken in claiming that John Lennon is playing, of all things, a slide guitar:

“The first song on the album, ‘Why,’ is an extended vocal exercise in which Yoko screams, cackles, howls, and laughs the title word over and over, with John playing a haunting slide guitar in the background. ‘Even we didn’t know where Yoko’s voice started and where my guitar ended on the intro,’ he shared. ‘It became like a dialogue rather than a monologue and I like that, stimulating each other.'”

Brackett quotes a musician who does know a lot more about guitar playing in his own review of “Why”:

“Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas was most impressed with Lennon’s musicianship on the album: “[He] was always able to make his guitar talk. He was one of the most visceral from-the-gut rock guitarists of all time. But never more so than on ‘Why,’ where his guitar spits lovely, processed shards of metal to inspire Yoko Ono’s uninhibited caterwauling. This is some of the most radical guitar soloing of the era, rivaling Lou Reed’s ‘I Heard Her Call My Name,’ Syd Barrett’s ‘Interstellar Overdrive,’ and Robert Fripp on ‘Cat Food’ for sheer conic bravado.’ But Yoko’s voice is without a doubt the star of her album.”

Cashbox magazine reported:

“Yoko Ono sums up the philosophy of the age as succinctly as anybody yet has in her first two sides here, ‘Why’ and ‘Why Not.’ Mrs. Lennon’s voice is the most interesting new instrument since the Moog Synthesizer and she uses it throughout.”

Duncan Fallowell reported in the Spectator:

“The first track is the most ferocious and frantic piece of rock I’ve heard in a long time and sets the pace for much of the rest. The most extraordinary feature of all is Yoko’s high-pitched voice which she uses not for singing but for producing stream of vocal effects. This produces a whole new territory of sound which, in pop, she is alone in exploring with any thoroughness, and unless her voice has been fed through electronic modulators she has quite remarkable tonsils. But I doubt this album will receive the attention it deserves, such is the antipathy toward Yoko Ono that she can do no right. Yet why she should be the object of such derision and plain insult I have never been able to understand. A couple of odd films and odd records hardly explains it.”

In 1970, when this album was released, these few critics responded to it favourably. Most of them treated it as a curiosity and shrugged if off as another example of Ono’s banzai banalities. But even now, 53 years later, it is still way ahead of its time, and has grown in public appreciation by both critics and the public. I find that I can never listen to the one single song, “Why”. I am drawn to listen to the entire album. Follow the instructions on the label of the original UK LP: PLAY IN THE DARK:

Ono has remarked facetiously that she already knows what the newspapers will write about her as an epitaph. She has lived through more negativity in the press than any other artist or entertainer, and sadly the hate levelled against her was often tainted with racism and misogyny. However I believe that the public opinion of her has changed since she made that prescient statement about her own demise. I like the way Brackett ended the book:

“She has been both a brave individualist who lived her life as art, and a sometimes savvy, sometimes naive creator of a Warholian public image that has taken on a life of its own. If recent years are any indication, she will be appreciated in both dimensions as an enigmatic, gifted, generous, quirky, surprising, thought-provoking, paradoxical, and thoroughly mesmerizing presence, and a mirror not only of her own times but of times to come.”

Find this book in the Mississauga Library System's on-line catalogue

No comments:

Post a Comment